The long drive to Qalqilya has convinced me that occupied Palestine is a giant obstacle course. A massive putt putt golf course where the Palestinians are the golf balls. I traveled to Qalqilya from Nablus. The first stop (pictured) was Beiteba Checkpoint just south of Nablus where, yet again, an Israeli soldier queried my nationality. I even discovered, firsthand, that the revolving door which is used to farm people through the checkpoint one-by-one has a device to stop it revolving. This quickly and efficently converts the revolving door into a tiny prison cell. I'm sure some American company devised that nifty little gadget so the poor Israeli soldiers don't get overburdened with those teeming Palestenian masses.

After I passed Beiteba I caught a service taxi to Qalqilya. Okay, so that's that. Or so I thought. But no. After around 20 minutes of 'nifty' service taxi driving we were stopped by a small Israeli checkpoint (pictured above) manned by what appeared to be very young Israeli soldiers.

Me: "Excuse me... excuse me, can I take a picture of you?" Click! With that I took the photo posted below.

Soldier One: "No, no-"

Soldier Two: "What, why you want to take a photo?"

Me: "Because it's cool."

Soldier Two: "Because it's cool? Who are you, [something in Arabic]-"

Me: "Sorry I don't speak Arabic, only English. I'm from Australia."

Soldier Two: "Are you Muslim."

Me: "Yes."

Soldier Two: "Let's see your passport."

Soldier Three (another soldier who hitherto had been speaking with the driver on the other side says to him): "Okay, you can go!"

[Car drives through whilst Soldier Two looks on, still quite keen to get my passport.]

Of course those words cannot adequately capture the incredible sense of intmidation you feel when two tall, armed-to-the-teeth and very cocky young Israeli soldiers speak to you like that. I should also point out that Soldier One (the one pictured above) actually pointed his gun at me briefly, and quite non-chalantly at that.

As the taxi sped off, I couldn't help thinking what wicked things guns are. To be sure there is more to this situation, any situation where a gun is involved. But in my experience with the Israeli soldiers, and with the Palestinian kids brandishing guns in Nablus, I saw first hand how dangerous these instruments of death were. Not only because they can kill, but because they give the wielder the arrogance to believe that they are some sort of authority unto themselves. I hate guns. Really fucking hate guns. They always make me nervous.

The taxi was stopped at another checkpoint just outside Qalqilya. This time the Israeli soldiers did take my passport, all of our passports.* Eventually they returned. In the mean time several Palestinian cars drove past without the Israel soldiers even turning to look at them. It was clear to me how random the checkpoint stops were. When the soldiers returned with the passports they motioned one of the men inside the taxi to get out. I watched as he was told to stand alongside the road, inside an area enclosed by a small metal roof and concrete barricades. The taxi sped off. Very random these checkpoints...**

Mohammed, a young activist from the area, was waiting to meet me when the taxi finally arrived in Qalqilya. It was a bright, hot, quiet day in the city centre. The conditions helped heighten the sense that I was now in the eye of the storm, that region of any large disturbance which is misleadingly calm. Qalqilya is quite literally, and quite breathtakingly surrounded by the separation wall. The wall is 120 metres within Palestinian territory as defined by the 'Green Line' of 1967.*** The wall has video cameras every 20 or 30 metres which you can see in the photos if you look closely.

Mohammed explained, "Qalqilya is the testing ground for the Israelis. The wall was first built here. I think Qalqilya is the only place where there are video cameras covering every inch."Israel says that the wall was placed around Qalqilya to stop terrorists from entering its territory from the West Bank. Yet none of the suicide attackers have ever come from Qalqilya. Moreover, as has been explained to me on a number of occasions now, there are several ways to get into Israel so as to avoid the separation wall and the endless checkpoints. Indeed, many thousands of illegal Palestinian workers travel to cities in Israel to work on a daily basis this way. The Israelis know this. It is an open secret. If the Palestinians wanted to commit a suicide attack in Israel they could do it almost at will. Is it then a coincidence that Qalqilya also happens to have some of the richest sources of subterranean water in the region? Whilst Israel has refused to allow the Palestinians to purchase new motors to pump the water, another example of Israel’s control over daily Palestinian life, the surrounding Jewish settlements have new water pumps working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Mohammed told me that the Israeli side of the separation wall is raised so Israeli soldiers and police can peer over it. Whilst Mohammed and I walked the length of the fence pictured above, we heard the dull sound of jeep tyres scraping towards us. Mohammed was clearly a little distressed, although he tried to conceal it.

"Ok, no problem. Let's keep walking."

Mercifully, the jeep didn't stop. Eventually we reached the beginning of the wall, an area intersected by a road lined on the Palestinian side with rubble and the occasional structure with tired, blistered shop signs in Arabic and Hebrew.

"Along here there used to be several shops. Israelis used to come here to shop. That's why the signs are also in Hebrew... One night the Israelis came and bulldozed all the shops."

The few shops that did not get destroyed were never opened again. Once the area was closed off from Israel business seized to exist. Now the area is an eerie ghost town (pictured below).

Qalqilya is still connected to a few surrounding villages through tunnels built under the wall by the Israelis. This has improved access for the local Palestinian population, although in the process of creating the tunnels Israel has confiscated further Palestinian land.  It seems there are no free lunches in the occupied territories, Jewish settlers excepted. The wall around Qalqilya was built at a sporadic rate. Mohammed believes this was done deliberately to heighten the sense of insecurity in Qalqilya.

It seems there are no free lunches in the occupied territories, Jewish settlers excepted. The wall around Qalqilya was built at a sporadic rate. Mohammed believes this was done deliberately to heighten the sense of insecurity in Qalqilya.

(This is the main access point between Qalqilya and Israel, although it is presently closed. Israel is currently building several warehouse-like buildings at checkpoints like this (see the white building behind the tower to the right in this photo) to process a significant pool of cheap Palestinian labour. I got shouted at by one of the soldiers in this tower after taking the photo. For a second I seriously thought I was going to be shot at.)

"Sometimes they build quick, sometimes they build slow. At first people just thought the wall would be small [not surround the entire city]... The slow construction made people think this. Eventually people could see that it was around Qalqilya, that they were in a big jail."

And so around 42,000 Qalqilyans are surrounded, along with around 40,000 others who live in villages just outside Qalqilya.

(Farming has increased in Qalqilya since the separation wall was erected and Palestinians were prevented from leaving the city. Prior to that, most of Qalqilya's workforce worked in Israel. At present unemployment hovers at around 60-70%.)

Qalqilya wall art

Sharon (here depicted as a pig in a suit) is bottling the Palestinians, one (city) at a time.

* In truth the Palestinians don't have passports for the checkpoints, although they do have passports for international purposes. Instead they have a rather macabre identification card which lists their name, father's name, place of birth and religion. Even within their own land the Palestinians have to provide identification to the Israelis.

** Here's another checkpoint story I can't help sharing with you. On my way out of Qalqilya, one keen Israeli soldier commented that my visa had expired. Having noticed where he was looking in my passport, I politely noted that he was looking at an old Pakistani visa. "Mate, you might want to check my Israeli visa stamp." One of his colleagues had to tell him that he was looking at the wrong visa. On the way out of Nablus a (rather attractive Ethiopian) Israeli soldier did something similar when she asked me whether I had a visa. I said she could check my passport herself, after all she was holding it. But rather than doing this, she merely handed the passport back to me. These episodes make me query the efficacy of all these Israeli checkpoints as a security measure.

*** The Green Line represents the boundary of the State of Israel prior to the 1967 war with neighbouring Arab states. In 6 days in 1967 Israel occupied the areas of Palestine now known as the West Bank and Gaza. Under international law, it has widely been accepted, including by no less an authority than the International Court of Justice, that Israel must withdraw to its territories within the Green Line. More information on the Six Day War are available here.

Today is my final day in Palestine. After that I'm off to crazy Cairo for half a day before embarking on the long journey back to Canberra, Australia. Yes, that's right, I'm returning to Canberra and my house negro ways. More on that later.

Today is my final day in Palestine. After that I'm off to crazy Cairo for half a day before embarking on the long journey back to Canberra, Australia. Yes, that's right, I'm returning to Canberra and my house negro ways. More on that later.

After I passed Beiteba I caught a service taxi to Qalqilya. Okay, so that's that. Or so I thought. But no. After around 20 minutes of 'nifty' service taxi driving we were stopped by a small Israeli checkpoint (pictured above) manned by what appeared to be very young Israeli soldiers.

After I passed Beiteba I caught a service taxi to Qalqilya. Okay, so that's that. Or so I thought. But no. After around 20 minutes of 'nifty' service taxi driving we were stopped by a small Israeli checkpoint (pictured above) manned by what appeared to be very young Israeli soldiers.

It seems there are no free lunches in the occupied territories, Jewish settlers excepted. The wall around Qalqilya was built at a sporadic rate. Mohammed believes this was done deliberately to heighten the sense of insecurity in Qalqilya.

It seems there are no free lunches in the occupied territories, Jewish settlers excepted. The wall around Qalqilya was built at a sporadic rate. Mohammed believes this was done deliberately to heighten the sense of insecurity in Qalqilya.

Forget ostensible explanations. This is a land grab.

Forget ostensible explanations. This is a land grab.  * It turns out both Pat and my parents live in the same suburb of Sydney. Talk about a small universe.

* It turns out both Pat and my parents live in the same suburb of Sydney. Talk about a small universe.

Another mountain around Nablus also has an Israeli base on top of it. Pat, an Australian law student teaching English and learning Arabic here, told me that the top of this mountain (circled in the picture below) is used by Israeli snipers. These snipers usually aim, extra-judicially as they do, at suspected militants. However, they have even killed children and elderly persons! The things you don't hear about on CNN...

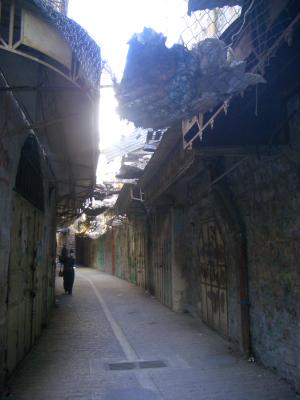

Another mountain around Nablus also has an Israeli base on top of it. Pat, an Australian law student teaching English and learning Arabic here, told me that the top of this mountain (circled in the picture below) is used by Israeli snipers. These snipers usually aim, extra-judicially as they do, at suspected militants. However, they have even killed children and elderly persons! The things you don't hear about on CNN... The old city of Nablus has a great deal of character. Sadly, it is the sight of routine skirmishes between the Israelis and Palestinian militants. Because of this, the alley-like walkways of the old city are marked with bullet holes and generally are in poor condition.

The old city of Nablus has a great deal of character. Sadly, it is the sight of routine skirmishes between the Israelis and Palestinian militants. Because of this, the alley-like walkways of the old city are marked with bullet holes and generally are in poor condition. Several nights each week, Israeli soldiers sweeped through the narrow streets of the old city in armoured vehicles. This inevitably leads to fierce gun battles with local militants, most of whom are with Islamic Jihad or Fatah. I had a Turkish bath last night in the old city as a gun battle raged briefly above.

Several nights each week, Israeli soldiers sweeped through the narrow streets of the old city in armoured vehicles. This inevitably leads to fierce gun battles with local militants, most of whom are with Islamic Jihad or Fatah. I had a Turkish bath last night in the old city as a gun battle raged briefly above.